In cardiorespiratory training, we can manipulate a number of variables to alter the intensity of the exercise and develop different energy systems. Below are some general guidelines on how you can manipulate these variables to meet your goal: The intensity and therefore how you manipulate these variables is dependent upon your goal. In strength training, we can manipulate a number of variables (load lifted, recovery time and the number of repetitions and sets) to alter the intensity of the exercise. The intensity of your training will also differ depending on the type of training you’re doing and your goal… This refers to how hard you work during a training session. Knowing this may inform how frequently you do certain exercises and how you structure your strength training sessions around your sport. It’s also important to be aware that the upper body may recover more quickly to heavy loading than the lower body and we can recover more quickly from single-joint movements (e.g., leg extension) when compared to multi-joint movements (e.g., squat).

This means if you do a split routine (i.e., upper body one session and lower body in a different session) you can train more frequently than if you do a whole-body workout in each session. As a rule of thumb, we should have at least one rest or recovery day (but no more than three) between sessions that fatigue the same muscle group. We can also follow some general guidelines for how frequently we can engage in strength training in sport. This means their body needs more time to recover so they are not able to train as frequently.

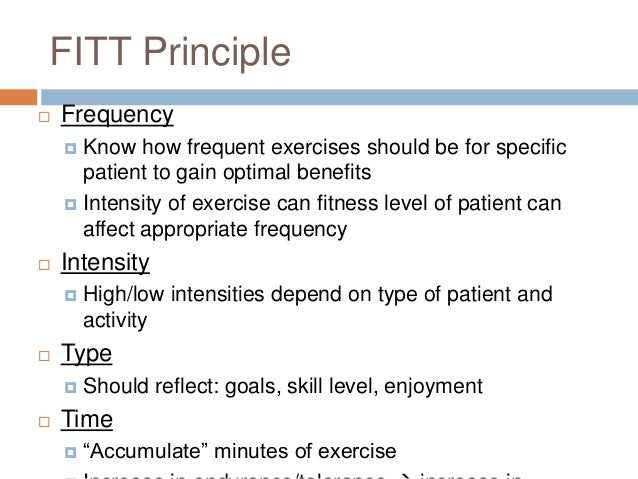

If we compare this to a footballer who has to jump and run constantly, their body is making repeated impacts with the ground (i.e., it’s a high impact sport) which is taxing on the body. This means they’re not putting much stress on their joints, bones and muscles so they can train more frequently. For example, a rower can train multiple times per day because it’s an impact-free sport. The frequency of sports training is dependent upon the type of training. However, if the athlete has a high training age, they are more likely to need more of a stimulus and thus, require them to train more frequently. If we take an athlete with a low training age, if they engage in some form of training once or twice per week, they are likely to get an adaptation from it as their starting base is low, their body will adapt to it. For adults aged 65+, they should also engage in balancing activities twice per week to reduce the chance of frailty and falls.įor an athlete, the frequency of their training may depend on their training age (i.e., the cumulative amount of time spent doing a specific type of training), the type of training they are engaging in, the intensity of the training and the time they need to recover. Let’s break the meaning of the FITT principle down further and explore each component… Frequencyįor the general population, UK guidelines recommend strength training on at least two days a week and at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise spread across the week. The four components are interconnected and how we manipulate them within a training programme, will influence the outcome of that programme.

These are four components that we can consider when creating a training programme. The FITT principle stands for frequency, intensity, time and type of exercise.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)